Directional Quotation Marks, Primes, & Unidirectional Quotation Marks

DISCUSSION OF TERMINOLOGY & PRACTICE

This opening guidance on setting quotation marks comes from the Chicago Manual of Style 16, which uses four different terms for the preferred character pair at the outset.

6.112 Typographer’s or “smart” quotation marks

Published works should use directional (or “smart”) quotation marks, sometimes called typographer’s or “curly” quotation marks. These marks, which are available in any modern word processor, generally match the surrounding typeface. For a variety of reasons, including the limitations of typewriter-based keyboards and of certain software programs, these marks are often rendered incorrectly. Care must be taken that the proper mark—left or right, as the case may be—has been used in each instance.

This post privileges the terms “directional” and “unidirectional” as we catalog variants.

Directional quotation marks—alternately known as typographer’s, typographic, typeset, curved, curly, or smart.

Unidirectional quotation marks; alternately known as neutral, vertical, straight, typewriter, ambidextrous, programmer’s, or dumb.

(If there are alternates that we have missed, please let us know.)

In working parlance at Blackbird, we are more likely to say “typographical” and “typewriter” rather than “directional” and “unidirectional.” I had come to prefer “curved” vs. “straight” because of the clear visual that language evokes. That said, this BirdLab post is meant to help us determine what language to use in our own style book, a decision not helped by Chicago’s choice to head their passage “typographer’s” and then to use the term “directional” in the opening sentence below the header.

I am decided on one point: quotation marks are neither “smart” nor “dumb,” though these are popularly used—if misleading—terms. More on this to follow.

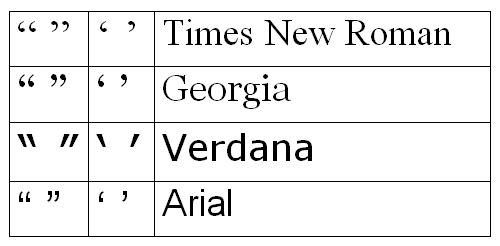

Here are four examples of opening and closing directional quotation marks in serif and sans serif fonts, including Blackbird‘s preferred body font, Verdana. (Note that the right single quote is the same as an apostrophe and is not otherwise discussed in this post.)

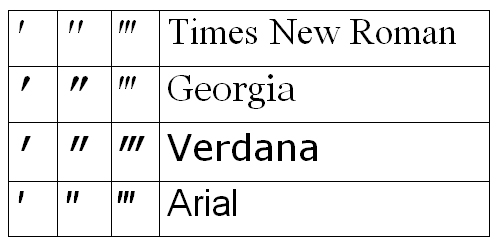

For purposes of disambiguation, here are prime marks for these same four fonts. The following passage is quoted from the Wikipedia article on prime marks, which provides more complete coverage for pagebuilders than any mention of primes in Chicago.

The prime symbol ( ′ ), double prime symbol ( ″ ), and triple prime symbol ( ‴ ), etc., are used to designate several different units and for various other purposes in mathematics, the sciences, linguistics and music. The prime symbol should not be confused with the apostrophe, single quotation mark, acute accent, or grave accent; the double prime symbol should not be confused with the double quotation mark, the ditto mark, or the letter double apostrophe. The prime symbol is very similar to the Hebrew geresh, but in modern fonts the geresh is designed to be aligned with the Hebrew letters and the prime symbol not, so they should not be interchanged.

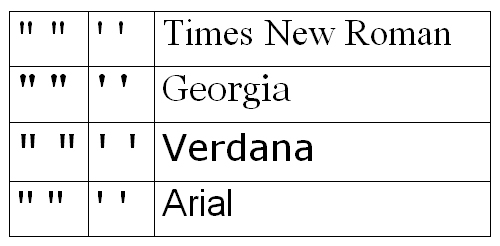

The primes are given here for comparison to the unidirectional quotation marks (fig 3) inherited from typewriter technology. Generally, we would call them “straight” or “typewriter” quotes but the term “ambidextrous quotes,” is a fitting historical descriptor as these figures are used on the typewriter keyboard to stand in for either prime marks or quotation marks. (“Ambidextrous quotation marks” is a term from Wikipedia’s article on quotation marks; I’m searching for uses of this language in other sources to see if it comes from typesetters or programmers.)

Unidirectional quotation marks (standing in for directional quotation marks or primes) should never appear on a page of Blackbird text; convert to the proper character in context.

David Dunham cites himself in an online page as the first person to write code to swap unidirectional quotation marks for directional quotation marks as early as 1986. Dunham writes

“Smart Quotes” is the automatic replacement of the correct typographic quote character (‘ or ’ and “ or ”) as you type (' and "). It does not refer to the curved quotes themselves.

Dunham confirms what I’ve been teaching for years: “smart quotes” refers to the automated conversion process, not to a set of characters themselves. This popular misuse has lead to the reverse labeling of unidirectional quotation marks as “dumb quotes,” but not in our shop.

When copyeditors encounter a contributor manuscript with unidirectional quotation marks, they note it on a paper copy. When the manuscript copyedits from multiple editors are reconciled to a digital final form for pagebuilders, the reconciling copyeditor applies the Microsoft Word “smart quotes” macro to the document to properly format quotation marks and apostrophes.

At the next step of copyflow, when the document lands in the digital “final for pages,” folder, pagebuilders must again revisit quotation marks upon converting them to HMTL. Information on this process will appear in an upcoming post

(For those with access to the online Chicago Manual of Style, read more at Special Characters.)

Also be aware that some systems, like WordPress (on which this blog is published) apply a “smart quote” filter to convert unidirectional quotation marks to directional; in draft, I see unidirectional quotation marks; on publication they are converted to directional quotation marks.

In this environment, if I actually want to display a unidirectional quotation mark, as in one instance of the Dunham quote above, I have to overtly mark up the unidirectional characters to keep them from auto converting. Be aware that this kind of auto conversion may muddle online discussions of this issue if an example of a unidirectional quotation mark is rendered, inadvertently, as directional. (I’ve seen this very problem more than once.)

<code>'</code> and <code>"</code>

FOLLOWUP

Blackbird is careful to always set directional quotation marks, but we need to agree on preferred language for in-house style and production manuals.