Leading by example: Alumna recognized as a nursing pioneer for service at Tuskegee Army Air Field

Daughter recounts experiences of her mother, a St. Philip alumna, who was a nurse and First Lieutenant at Tuskegee Army Air Field.

Many now know the storied history of the Tuskegee Airmen and their service to the country as the first Black military pilots in a segregated U.S. Army during World War II. Perhaps lesser known are the experiences of the first Black nurses commissioned into the Army, who served to support segregated bases and units like those at Tuskegee Army Air Field.

Before the United States became involved in World War II, pressure from Black civil rights organizations and professional nursing associations like the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) mounted, advocating for Black Americans to participate in the country’s war efforts.

When [Louise Lomax Winters and other St. Philip’s alumnae] were met with unjust discrimination and prejudice, they responded with persistence and resolve.

– Jean Giddens, Ph.D., dean of the VCU School of Nursing

In 1941, the Army Nurse Corps became the first U.S. military branch to allow the admission of Black nurses into their ranks. This highly visible opportunity attracted the attention of many new Black nursing graduates around the country, like Louise Lomax Winters who graduated from St. Philip’s School of Nursing in 1942, which was the segregated nursing school established by the Medical College of Virginia.

Determined to serve

Winters, who grew up in Nottoway County, Virginia, was the oldest daughter in a family with five children. As a young woman, she helped to take care of younger siblings and, at times, traveled to New England as a live-in housemaid. She pursued a nursing education in part to professionalize her natural caregiving instincts and skills, but also to enter a career that could provide ample support for herself and two younger sisters, whose education she helped to fund.

When she learned about the opportunity to join the Army Nurse Corps, she was determined to be considered for the job. A path to securing that commission however, was far from clear.

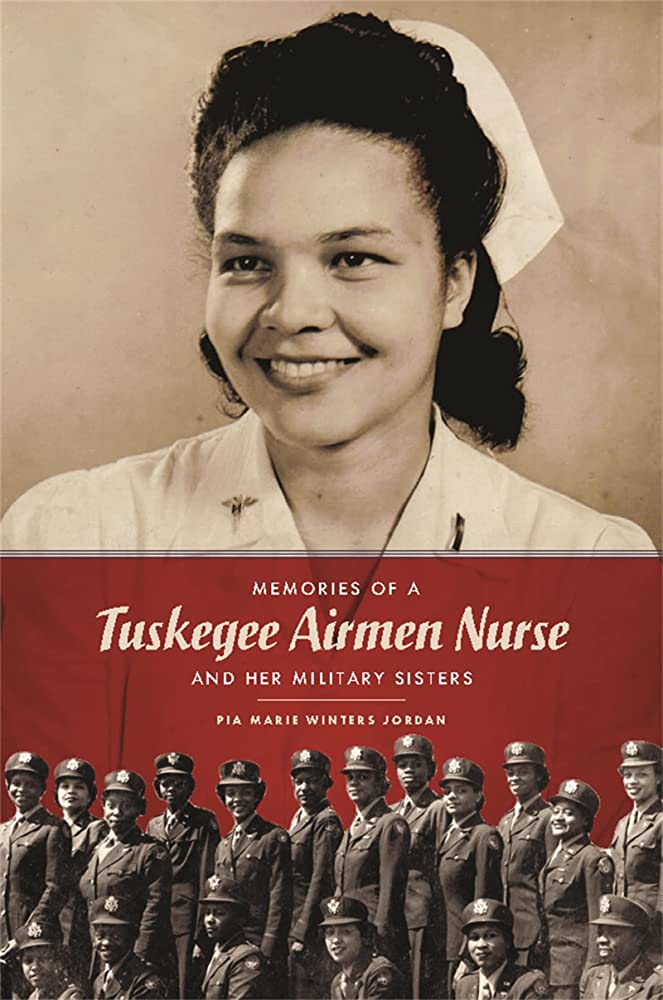

“She had to write to the NACGN, the organization that helped oversee Black nurses, because she was having trouble getting through. It seems everyone was kind of slow allowing African American nurses to participate in the Army Nurse Corps,” said Pia Winters Jordan, Winters’ daughter who has detailed her mother’s experiences in a forthcoming book, “Memories of a Tuskegee Airmen Nurse and Her Military Sisters.”

The front cover of the book “Memories of a Tuskegee Airmen Nurse and her Military Sisters,” written by Pia Marie Winters Jordan. The book details her mother’s experiences during WWII.

(Contributed by Pia Marie Winters Jordan)

Eventually, she received notice that she would be commissioned as a nurse and Second Lieutenant at Tuskegee Army Air Field, site of the only training facility for Black pilots at the time.

At any given time, there were about 20 nurses staffing the station hospital at Tuskegee Air Field and they came from more than a dozen nursing schools from across the country, including St. Philip School of Nursing, the segregated nursing school established by the Medical College of Virginia in 1920. Remarkably, four Tuskegee nurses were St. Philip’s-educated: Della Bassett, Norma Greene, Mencie Trotter and Winters.

“The determination Louise Lomax Winters and other St. Philip’s alumnae demonstrated in seeking out opportunities like the U.S. Army Nurse Corps is truly admirable. When they were met with unjust discrimination and prejudice, they responded with persistence and resolve,” said Jean Giddens, Ph.D., professor and dean of the VCU School of Nursing and Doris B. Yingling Endowed Chair. “The VCU School of Nursing is proud of these remarkable women and their place in history.”

Success despite facing discrimination

With the commission to join the unit, Winters and her fellow nurses received acknowledgement of their professional abilities by the U.S. government that they had always deserved. But in other ways, the burden of racial segregation and discrimination persisted.

“Black cadets and nurses were not really welcome in Tuskegee, Alabama. Their life was on base. They were resented by the surrounding local community,” Jordan said.

Daily life at Tuskegee Army Air Field included nursing shifts and military protocols but also recreational activities like the on-base movie theater and touring performances by musical acts. For those nurses who had grown up in or spent time in the southern U.S. where Jim Crow laws legalizing racial segregation were in effect, the experience of being segregated on an all-Black base was perhaps more familiar.

“When they left the base, my mother said there were a few incidents. Even though they were in a uniform, the community surrounding the base saw them as something else,” Jordan said.

When the U.S. military finally extended combat and leadership roles to Black Americans, there was a prevailing belief that it did so intending for them to fail, not yet ready to desegregate and reckon with its discriminatory infrastructure and laws. Of course, quite the contrary unfolded as the Tuskegee Airmen earned early and unmistakable success in combat. The pilots trained on base famously recorded one of the lowest loss records of all escort fighter groups, and came to be in demand supporting allied bomber units. That success is owed to the collective effort of the base personnel who supported them during training, including nurses like Winters.

“Just think, if [the nurses at Tuskegee Air Field] had not done well, and if the Tuskegee airmen had not performed well, that we may not have had an integrated military. President Truman, by an executive order later in 1948 integrated the military […] These women, they were able to prove themselves and that laid the foundation for future African American nurses in the military,” Jordan said.

A storied career and legacy

About 500 Black nurses served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps through the end of WWII. Promoted to First Lieutenant by 1946, Winters continued her service at Tuskegee Air Field and was one of the last five nurses on base when it was designated for closure in July 1946. She was honorably discharged from active service in 1949 and then the reserves in 1953. Following her active military service, she worked in civilian and veterans hospitals in Michigan, Maryland and Illinois, ultimately retiring from the profession as a psychiatric nurse in 1973. She died in April 2011 and shortly following a scholarship was established in her honor at the VCU School of Nursing.

“I saw that the Tuskegee Airmen were not the only ones making Black history during World War II, but the nurses had to fight gender as well as racial discrimination. Through my research, I found out more about them. It was time for their story to be told,” said Jordan.

Winter’s remarkable service as one of the first Black nurses in the Army Nurse Corps is a testament to the lessons she took with her from St. Philip School of Nursing to Tuskegee, Alabama and her undaunted pursuit in being recognized as an excellent nursing professional. In many ways, that service is memorialized in the Class of 1942 motto printed in her St. Philip’s yearbook: “Be not simply good, but good for something.”

By Caitlin Hanbury

Categories Alumni and Friends, News